Public Sector and Meta dependencies – input from the Nordics

Why Nordic municipalities are rethinking their relationship with social platforms.

On November 27, 2025 Sweden's publisher organization Utgivarna filed a police report against Mark Zuckerberg. The charge? Facilitating financial and psychological harm through Meta's consistent failure to prevent fraudulent advertisements exploiting Swedish public figures.

This marked a turning point in how Nordic public sector organizations think about their dependence on Meta's platforms.

The scale of the problem

TV4's Olof Lundh captured it succinctly: "The sick thing is that it is allowed to happen completely openly on platforms owned by Meta."

The numbers are troubling. Approximately 10% of Meta's revenue, around 150 billion SEK in 2024 – allegedly comes from fraudulent advertisements. One documented scam network alone paid over 13 million SEK monthly for ads, with a significant portion flowing to Meta.

Meanwhile, Swedish municipalities spent at least 20 million SEK on Meta advertisements in the same year. Public money, feeding the same platform under investigation for profiting from fraud.

The irony: municipalities use Meta to build trust with citizens on the very platform where citizens are being systematically deceived.

The dependency dilemma

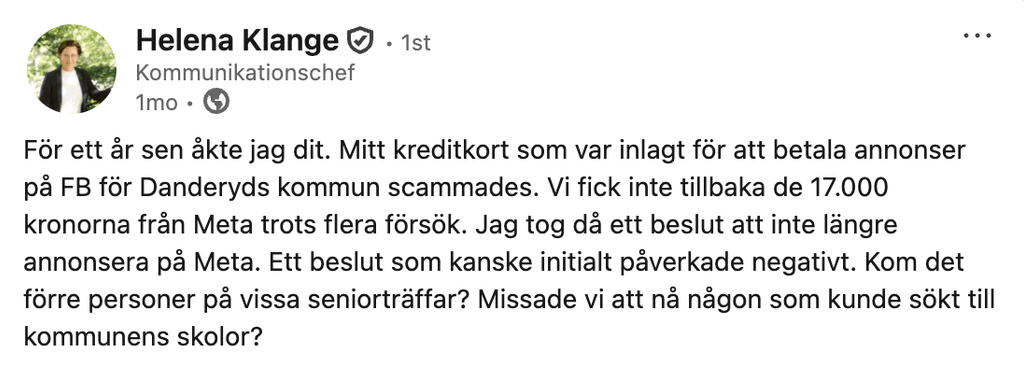

Helena Klange, a public sector communications professional, experienced this contradiction firsthand. After being scammed out of 17,000 SEK through Meta's advertising platform, she stopped all paid advertising on Meta.

But she couldn't leave entirely. "My constituents are there," she explained, illustrating the powerful network effect that creates dependency even for those who recognize the platform's problems.

This is the modern dilemma: How do you serve citizens where they are, without supporting systems that may harm them?

What dependency costs

1. Ethical compromises

Public organizations exist to serve and protect citizens. When they channel tax money to platforms under police investigation for enabling fraud, they face an ethical contradiction that's becoming harder to ignore.

SVT's Anne Lagercrantz describes repeated attempts to get Meta to act: "Innocent people are tricked by scammers. Our profiles and brands are exploited. We have tried repeatedly to get Meta to act, but the scams continue."

2. Trust erosion

When citizens receive official municipal communication on the same platform where sophisticated scams use AI-generated images of trusted figures to steal their money, the boundaries blur. Municipalities work to build trust. Meta's business model increasingly undermines it.

3. Strategic vulnerability

Municipalities relying primarily on Meta face algorithm changes that dramatically reduce reach, policy shifts that conflict with public communication needs, and platform instability that could leave them voiceless during emergencies.

Meta's response: "It violates our policy to impersonate companies and public figures, and we will remove these accounts when we become aware of them." Yet the scams continue at scale.

The Nordic response

What makes the Nordic approach distinctive is its clarity about public sector values. When Bydel Frogner in Oslo extended their partnership around the "Min Bydel" app with Innocode, they did so with an explicit position: the public sector should not be dependent on Meta for communication with residents.

This isn't anti-technology sentiment. It's a principled stance that public communication infrastructure should serve public interests, controlled by public entities – and that resources shouldn't subsidize platforms whose business practices conflict with public service values.

Other Nordic examples:

- Västerås (Sweden): 30,000 app downloads in year one, reaching 25% of residents directly

- Södertälje: Real-time data features make their municipal app genuinely useful daily

- Farsund (Norway): 30% reduction in contact center calls through owned-channel push notifications

- Oslo's "Min Bydel" districts: Building hyperlocal community channels independent of commercial platforms

These aren't just technical projects. They're strategic choices about public sector independence and citizen service.

Rethinking the relationship

The Nordic perspective increasingly centers on a principle: use social media, don't depend on it.

This means:

- Maintaining social media presence where citizens are active

- Building owned communication infrastructure municipalities control

- Redirecting advertising spend from rented visibility to owned assets

- Creating resilient systems that function independently during crises

- Ensuring public communication serves public interests, not platform algorithms

Moving forward

The police report against Meta's CEO, public criticism from Sweden's most trusted media figures, and growing municipal investment in owned channels all point to a broader reassessment of public sector digital strategy.

The question isn't whether Meta and other commercial platforms will continue to exist. They will. The question is whether public organizations will remain strategically dependent on them – or build the infrastructure needed to communicate with citizens on their own terms.

The Nordic answer is increasingly clear: public communication is too important to outsource entirely to commercial platforms with conflicting interests.

Sweden's experience – from the 20 million SEK in municipal ad spend to the police investigation of platform-facilitated fraud – offers a case study in why that independence matters.